Communication Arts chair presents photography exhibit honoring genocide victims

Photo credit/ Amanda Duncklee

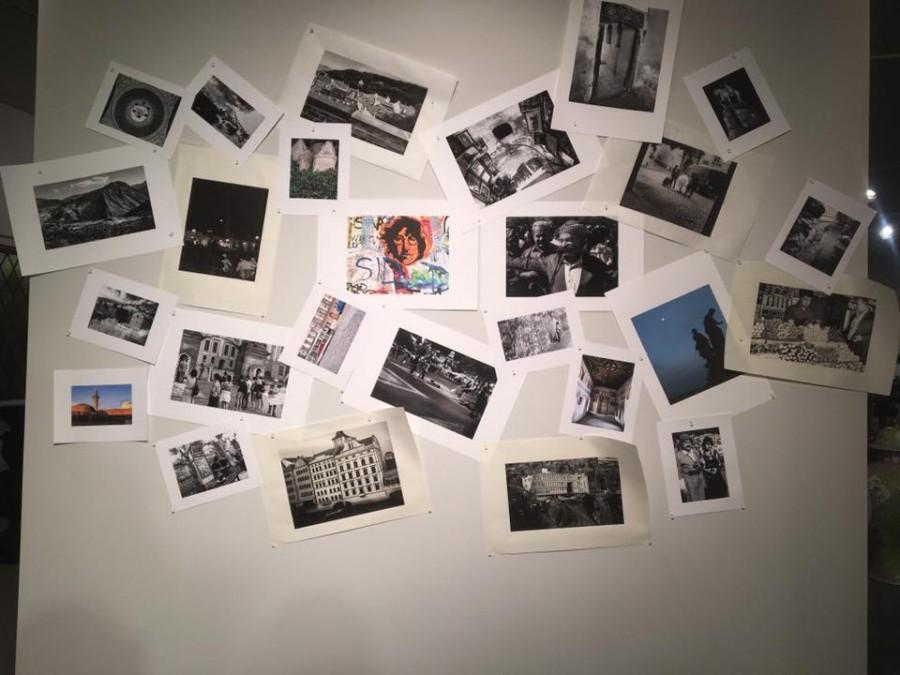

Photos of modern day life in the regions

February 18, 2016

Communications Arts Department Chair Dr. Michael Mirabito spent time visiting and photographing locations formerly and currently home to unspeakable horror in order to convey the need for humanity to right itself.

In his exhibit titled “Terezin and Kurdistan- A Journey,” Mirabito photographed prison camps from both regions, which are the sites of past and recent genocides. His exhibit is located in the Suraci Gallery within the Shields Center for Visual Arts until Feb. 28.

“We think that this can never happen anywhere in the world,” said Mirabito during his talk at 2 p.m. on Wednesday, Feb. 17, as a way to remind the packed gallery that genocide is not an atrocity of the past.

Along with Ernie Mengoni, director of broadcast operations, Mirabito traveled oversees over summer 2014 to capture photographs from the areas. Photographs include shots of the prisons representing devastation of the past as well as present day images of modern people.

Along the walls of the exhibit hung images from both regions. Toward the back of the exhibit, pictures of present day people are in a collage to represent how it is possibly for normalcy to return.

The photos of the concentration camps in Terezin and the prisons in Kurdistan are set on semi-gloss paper to accentuate colors and vibrancy in the photos. Those of joyful present-day people are set in matte, to represent life and normalcy in previously devastated regions.

The paintings were printed on thin Japanese paper with a white piece of paper in between the drawings and the names of the Holocaust victims the paintings were originally drawn on. In the right light, there appears to be a glow emanating from the paintings.

From the ceiling hung photographed paintings from prisoners in the Czech Republic.

“Out of all the horror, you still have these amazing drawings from these amazing people,” said Mirabito. In reference to his own photography and why the photos depicting joy are present, Mirabito said, “The photos are like the circle of life.”

In photographing haunted areas, Mirabito sought to shed light on regions of genocide that are not widely publicized.

Terezin was a fortress in the Czech Republic that Nazis overtook during World War II. The site, which Nazis used propaganda to portray the image of a cultural hub for artists and musicians, was in actuality the site of torture, death and unspeakable evil. Some prisoners were transferred to other camps while others died in Terezin, according to Mirabito’s biography.

Likewise, the region of Kurdistan in the country of Iraq experienced tragedy for the past few decades, according to Mirabito. Saddam Hussain commanded forces to ravage the area with murder throughout the region and chemical warfare in Halabja. Despite his execution in Dec. 2006, the Kurdish people are still suffering: terrorist groups ISIS/ISIL have targeted the region since 2014, resulting in the deaths of thousands.

Honar Ali, an art painting graduate student, has personal ties to one of the regions depicted.

“It’s about Kurdistan, and it’s my area so I wanted to see it,” said Ali, who had seen firsthand the prisons and the sites of chemical warfare. “When focused by an outsider, it’s interesting to me.”

Mirabito has future plans to document more regions of genocide as a way to remind people never forget the victims of genocide and to work to combat such evil. He plans on launching a website to further document his photography in the fall and plans on preparing for the launch over the summer.

“[Genocide] is an ongoing problem, said Mirabito. “We are the only ones who can stop it from occurring.”

Contact the writer: [email protected]

@ADuncklee_TWW