Comm Arts chair documents Dakota pipeline protests through photographs

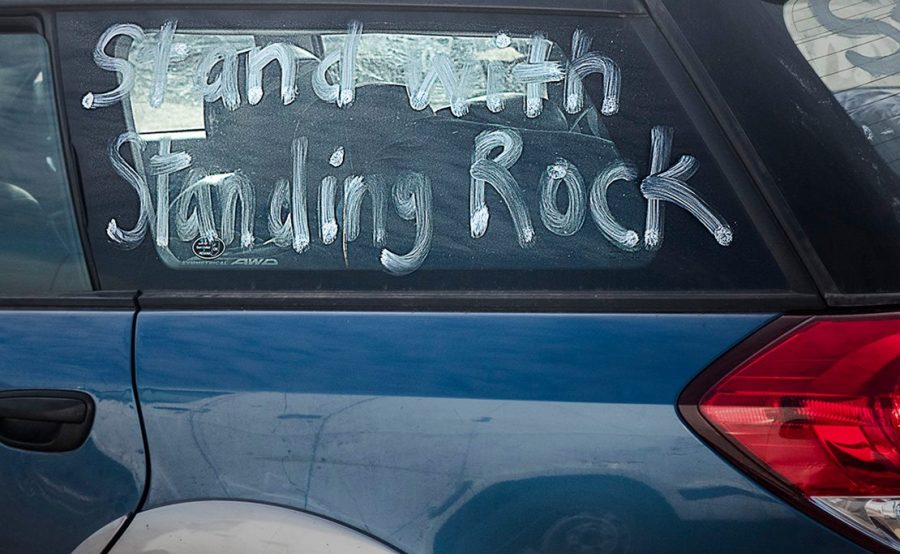

A car window was painted with the popular support phrase “Stand with Standing Rock.” Photo courtesy of Dr. Michael Mirabito (Copyright 2016)

December 2, 2016

In light of the ongoing protests concerning the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) construction, Communication Arts Department Chair Dr. Michael Mirabito recently traveled to the Standing Rock Native American Reservation in North Dakota to document the events through photos.

He plans to incorporate these photos into the new “Holocaust and Genocide Studies Center,” which provides visual education of historic holocausts and genocides throughout the world. Earlier this year, Mirabito presented a gallery depicting sites in Kurdistan, where thousands of people were killed during the rule of Saddam Hussein, and Terezin, a concentration camp in the Czech Republic still standing from World War II.

Additionally, Mirabito recently visited a site relevant to the Trail of Tears where Cherokee Native Americans were uprooted from their land in the late 1830s. During his trip to North Dakota, he traveled a few hours more to visit the site of the Battle of Little Bighorn, where combined Native American tribes fought against the U.S. army in 1876.

He hopes the project will bring more awareness to the events transpiring in North Dakota and how these events connect with American treatment of Native Americans in the past.

“We talk about genocides in Europe. We talk about the Holocaust, the Armenian genocide, what’s taking place in Africa, but we had our own with Native Americans,” Mirabito said. “While there was violence on both sides … we also wiped out people.”

According to the project developer, Energy Transfer Partners, the DAPL is a 1,172-mile, 30-inch diameter, underground pipeline that will transport approximately 470,000 barrels of domestically produced crude oil from North Dakota to Illinois per day. Since its planned path involves construction underneath the Missouri River, protesters from the Standing Rock Sioux tribe, as well as other tribes and non-Native American allies have set up camp outside of Cannon Ball, North Dakota since April 2016.

“There’s a lot of support for the tribe,” Mirabito said. “Actually, for the first time in years, tribes which never really dealt much with each other have gotten together in support of this operation. It’s sort of like a unified front by the tribes.”

Protestors oppose the pipeline because they believe it lacks sensitivity to Native American culture and can potentially have a negative environmental impact on the land.

The prospective route of the pipeline does not come into contact with the Sioux reservation, but it crosses federal land the Sioux once inhabited and used as burial ground. Mirabito said the U.S. government granted the Sioux ownership of this land with the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, but seized it back illegally years later.

Dr. Lia Richards-Palmiter, director of diversity efforts, said she believes the pipeline infringes upon Native American rights.

“To the indigenous tribes, it’s sort of, yet again, another sort of product of power and privilege that we have over the Native Americans,” she said.

After “taking the voice” of Native Americans for so many years, she sees this as another injustice against them.

“This infringes upon their constitutional rights,” she added.

As for the environmental impact, the Sioux population depends on the Missouri River for their water supply.

If the pipeline were to rupture, the river could become polluted.

“To Native Americans, the water has a sacred connotation to it as well,” Mirabito said. “So you’re not only potentially damaging their water supply, you’re also potentially damaging something that is held in high esteem to them.”

Violence between protesters and law enforcement has escalated since Mirabito’s trip, causing the Army Corps of Engineers to close all lands north of the Cannonball River to the public for safety concerns starting on Dec. 5. This will result in the tribe having to shut down one of their camps, Oceti Sakowin.

In its place, the Army Corps will allow a “free speech zone” south of the Cannonball River on Army Corps lands.

Currently, the construction of the pipeline’s segment underneath the Missouri River remains at a standstill until the Army Corps of Engineers gives their official approval to Energy Transfer Partners.

With the DAPL situation still ongoing and up in the air, Mirabito hopes to present another photo gallery in the future to educate others on the subject.

“With my pictures, I’m trying to give people another angle, or … perspective on a site and what took place at the site, and trying to keep that alive in people’s memories,” Mirabito said. “Some people learn and do better by reading. Other people do better by visualization and seeing things, so that’s the part I’m hoping to provide by taking pictures of these sites.”

Contact the writer: [email protected]